01/07/2026: News Guild Waived Right to Certain Washington Post Salary Information

Decertification petition dismissed.

There are two cases today, one an ALJ decision where it was determined the union had waived its right to name-linked salary information and another where it was determined that not enough bargaining had occurred to permit a decertification petition to proceed.

WP Company LLC D/B/a the Washington Post, JD-04-26, 05-CA-304158 (ALJ Decision)

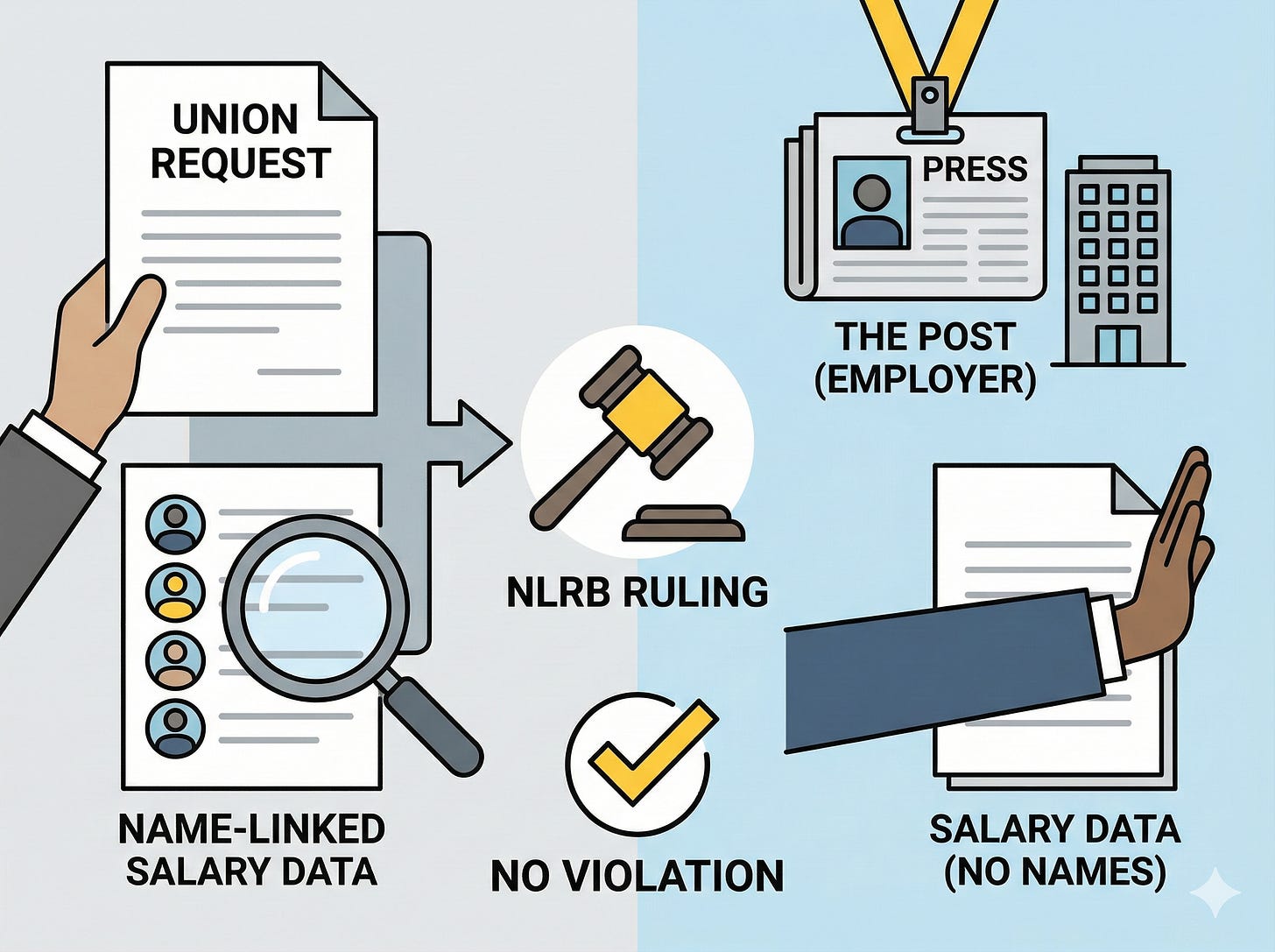

An NLRB Administrative Law Judge ruled that The Washington Post did not violate the NLRA when it refused to provide the Washington-Baltimore News Guild with name-linked salary information for bargaining unit employees. The General Counsel had alleged the newspaper violated Section 8(a)(5) and (1) by refusing verbal and written requests in August 2022 for employee names paired with salary data.

The union sought the name-linked information to evaluate pay equity and develop healthcare proposals during contract negotiations. While the judge found such requests presumptively relevant under established Board precedent, the decision turned on a 1989 settlement agreement resolving earlier information disputes. That agreement required the Post to provide detailed non-name-linked salary data—including department, job classification, demographics, and salary history—along with a separate employee name list, but explicitly limited the employer’s obligations to this non-linked format.

The judge concluded the union had waived its statutory right to name-linked data through multiple factors: the express language of the still-effective 1989 agreement, consistent bargaining history showing the union repeatedly proposed but ultimately abandoned demands for name-linked information during contract negotiations in 2005, 2014, and 2022, and an established pattern of requesting and accepting non-name-linked data since 1989. Though the agreement contained a non-admission clause preventing its use as evidence of waiver, the judge found the combination of contractual language, bargaining history, and past practice sufficiently demonstrated the union had consciously and unmistakably yielded on this issue.

The Post had consistently provided comprehensive non-name-linked salary data in electronic format, along with employee ID numbers allowing data linkage across reports, and did provide name-linked information for other matters like healthcare benefits and compensation beyond base salary.

Significant Cases Cited

Metropolitan Edison Co. v. NLRB, 460 U.S. 693 (1983): Established that waiver of statutory rights must be “clear and unmistakable.”

NLRB v. Katz, 369 U.S. 736 (1962): Held that employers have a duty to bargain over mandatory subjects including wages, hours, and terms and conditions of employment.

NLRB v. Acme Industrial Co., 385 U.S. 432 (1967): Established that relevance of information requests should be determined using a liberal “discovery-type standard.”

E.I. DuPont DeNemours & Co., 368 NLRB No. 48 (2019): Explained that waiver can be established through contract provisions, conduct of parties including bargaining history and past practice, or a combination of both.

Boston Herald-Traveler Corp., 110 NLRB 2097 (1954): Found employer unlawfully refused to provide union with name-linked salary information, noting full disclosure might reveal wage inequities the bargaining representative has right and duty to negotiate.

CCI Industrial Services, LLC, 19-RD-375698 (Regional Election Decision)

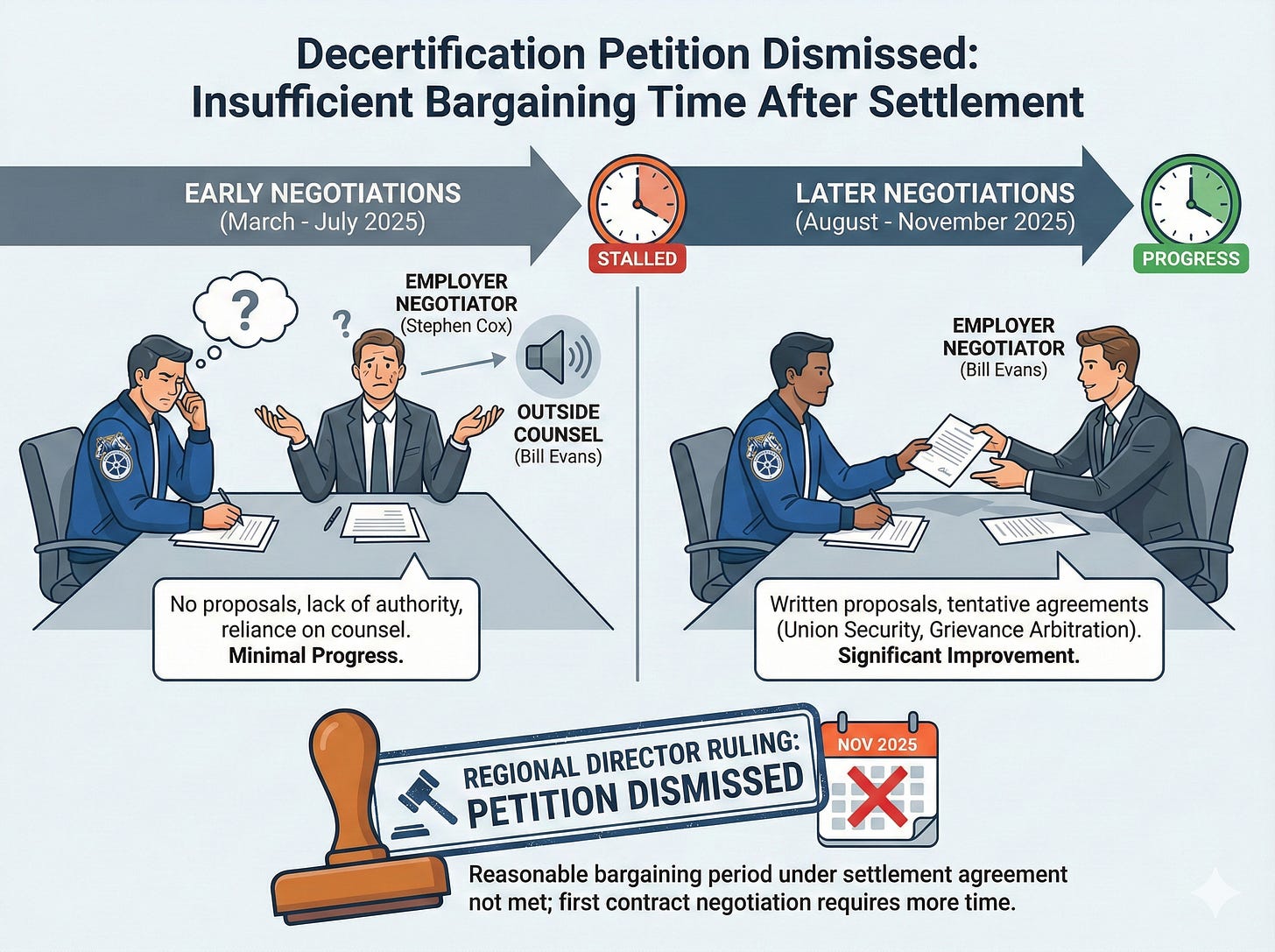

An employee at CCI Industrial Services filed a petition to decertify Teamsters Local 959 as the bargaining representative for mechanics and related employees at the company’s Alaska facility. The union argued the petition should be dismissed because an earlier settlement agreement requiring the employer to recognize and bargain with the union had not yet been given sufficient time to succeed. The regional director agreed and dismissed the petition.

The case arose after the union lost a 2024 representation election but then filed objections and unfair labor practice charges. In October 2024, the parties settled, with the employer agreeing to recognize the union and bargain. Bargaining began in March 2025 but proceeded poorly for months. The employer’s initial negotiator, Stephen Cox, had no collective bargaining experience, failed to present written proposals, repeatedly deferred decisions to outside counsel Bill Evans, and refused to provide copies of other collective bargaining agreements he referenced at the table. The union organizer testified that Cox appeared to lack authority and knowledge, requiring explanations of basic bargaining concepts. Between March and July 2025, the parties met 8 times with minimal progress.

In August 2025, Evans took over as the employer’s negotiator, and bargaining improved significantly. The parties began exchanging written proposals, reached tentative agreements on several provisions including union security and grievance arbitration, and started discussing economic terms. However, by the petition filing in November 2025, they had met only 6 times with Evans over 3 months, totaling about 12.5 hours.

The regional director applied the multi-factor test from Poole Foundry for determining whether a reasonable bargaining period had elapsed. Several factors weighed against finding sufficient time had passed: this was a first contract negotiation, which typically requires a longer period; the employer’s approach made bargaining unnecessarily complex; limited time had been spent in meaningful bargaining; and little progress occurred until recently. The director emphasized that genuine bargaining with a knowledgeable negotiator had only begun 3 months before the petition was filed, no impasse had been reached, and the parties were making progress. Under these circumstances, the settlement agreement still barred the election because insufficient time had passed for the parties to reach agreement.

Significant Cases Cited

Franks Bros. Co. v. NLRB, 321 U.S. 702 (1944): A bargaining relationship must be permitted to exist and function for a reasonable period to be given a fair chance to succeed.

Lee Lumber and Building Material Corp., 334 NLRB 399 (2001): Established a 6-month minimum and 1-year maximum bar on elections following unlawful refusal to recognize or bargain, and recognized that first-contract negotiations require longer reasonable periods because parties must establish basic procedures and core terms.

AT Systems West, Inc., 341 NLRB 57 (2004): Applied the multi-factor test for determining reasonable bargaining time including whether parties negotiated a first contract, complexity of issues, time spent bargaining, progress made, and whether impasse was reached.

Poole Foundry & Machine Co., 95 NLRB 34 (1951): Settlement agreements containing bargaining provisions must give parties reasonable time to actually bargain.

Textron, Inc., 300 NLRB 1124 (1990): The reasonable bargaining period is measured by whether parties have adequate opportunity to bargain rather than mere passage of time.